The two things about today's chaos that might keep you sane.

I don't know how the rest of you keep it together, but understanding this gets me through the worst of it. This is Part 1 of a three-part series on generations: Why it's actually supposed to be chaos.

This three-part series on generations is free and public; feel free to share. And—please!—if this rings bells for you, good or not, comment,❤️, share, or subscribe so we hear your voice on this mess.

While I write about women’s health after decades in the field, a while ago I also got deeply into generations theory, first to be able to engage women of all ages on health issues, and then because it’s just a great tool for communicating with anyone of any age or gender. It’s now my primary research and speaking focus.

People think “generations” means memes and yet another way of classifying people—something no one loves. What gets left out in the click-bait is the foundational generations theory—the part that isn’t a new way of bullying, and, better yet, provides a context for the chaotic era we’re experiencing right now in America’s history.

Part 1 looks at how generations theory provides context and reassurance about today’s political and societal chaos.

For starters, it’s not about who’s better, Millennials or Boomers.

Millennials and Boomers are today’s names for two generational archetypes that have always clashed over the 500+ years of our history we know about. Don’t you hate it when we’re not unique? I fought Myers-Briggs at first, too.

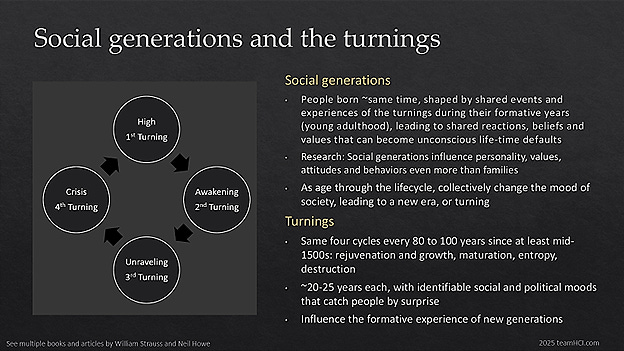

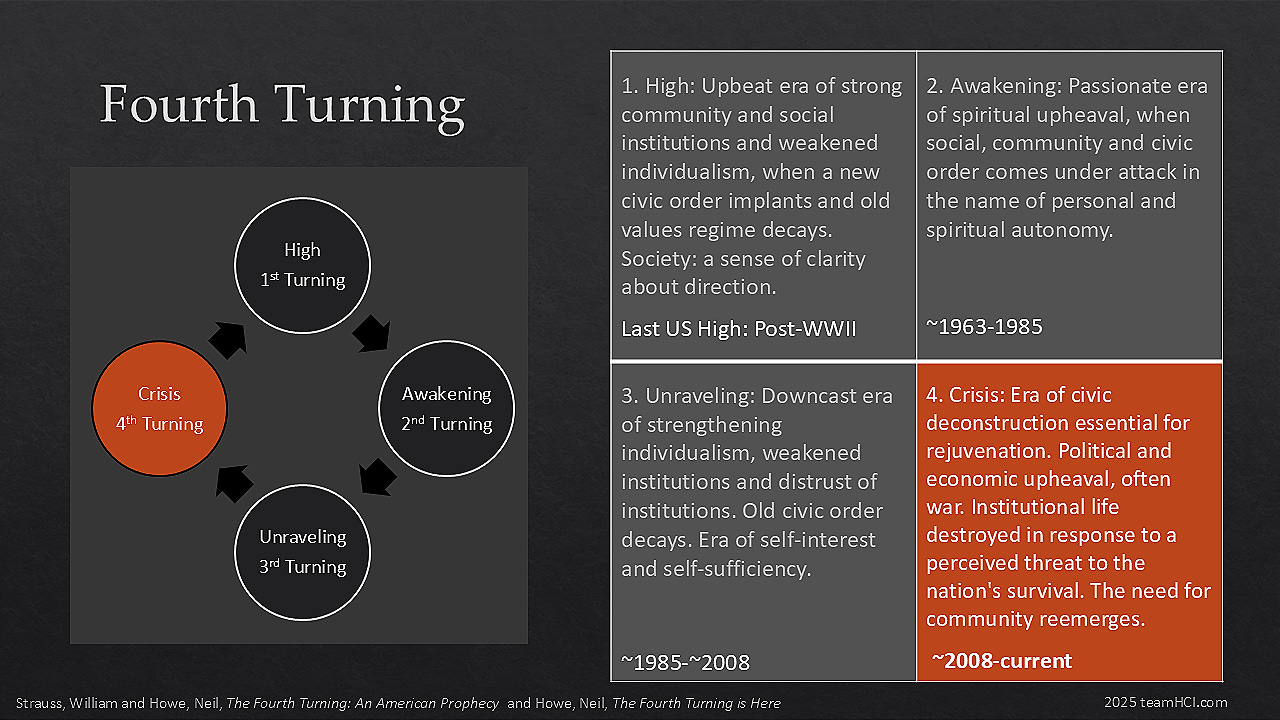

In short, generational theory says that history is cyclical, repeating the same general pattern of growth, maturation, decline and death or re-invention every 80 to 100 years or so. When it was first identified, the theory was based on in depth social and economic research on more than 500 years of Anglo-American history. Now we see that most countries and regions have gone through parallel experiences and reactions since the start of the industrial revolution in the mid-1800s.

The cycles will be familiar. If you’re into gardening, you know nature’s cycles. If you’re in business, you’ll recognize the well-understood business cycle. If you’re a human, and definitely if you’re a parent, you understand it innately.1

It’s life, and generational theory says the cultural and political season we’re in right now is winter—a very ugly winter, indeed.

18% of the US population is 65+. In the US Senate, it’s 50%. Pretend you’re a 30-year-old and give that some thought.

The good news about winter, of course, is that it eventually gives way to spring. And in history-based generations theory, when and how spring might come is fairly reliable.

But we‘ve never seen anything like this before.

Massive post-pandemic economic instability. Threats of war shattering American optimism about the future. Younger generations in rebellion against older generations seemingly committed to an orgy of greed and speculation. A barrage of new, unregulated technologies. Cultural conflicts pitting urban societies against rural. Cultural battlefields on immigration, drugs, military involvement, race, gender politics and sexual mores. Overt racism, xenophobia and nepotism among political leaders. Religious traditionalists pitted against modernists. A rising white Christian nationalist movement. Profound social upheaval with open challenges to laws, morals, ethics and civility, celebrated by some, horrifying many.

That was the 1920s and 1930s, and we survived it then, too. Deep breath.

So, no, unless you were born around 1910, we haven’t ourselves seen it this bad before. But we have been here before as a nation—several times—and it was just as ugly then, too.

And no, our grandparents didn’t have our 24/7 barrage of potentially poisonous social media. But radios were the hot new tech toy of American households then. Most homes had one by the 1930s and that exciting new medium was being used to spread the race-baiting, xenophobia, and hatred of immigrants that was the click-bait of the times. And Americans were every bit as attracted to that new tech marvel then as we are now to the still-new tech toy of social media.2

The anti-immigrant rancor then was aimed at a huge influx of Irish, Italian and Jewish immigrants, targeted primarily because they weren’t Protestant and lacked “native traditions.”3 And the rancor and political manipulation were at least as ugly under the US presidents who supported or upheld policies of racial discrimination at the time.

I love remembering it was only 40 years from the KKK’s frenzy of anti-Irish, anti-Catholic rioting of the ‘20s to the election of a Catholic US president descended from poor Irish farmers fleeing a famine. #America

So…there’s a chance we’ll make it through this?

Our great, positive, can-do American spirit prevailed in our other three fourth turnings.4 It’s up to us what our spring looks like this time, and how bad it gets before then … but a spring of some type will come.

A quote that helps me get through this mess almost daily is one attributed to Winston Churchill, the WWII-era UK prime minister who had plenty of experience with the US then as we very actively fought joining the war.

“You can always count on Americans to do the right thing … after they’ve tried everything else.” — Winston Churchill

I prefer to think of our current era as the period of ‘trying everything else’ first before we settle down and do the right thing. We will. We’ve shown that in our three prior swings at this.

What are the cycles?

The economic and social demographers and historians who did the foundational work on generations theory are William Strauss, now deceased, and Neil Howe. Howe is a highly respected economist and demographer who has authored several best-sellers since; he’s on Substack as Demography Unplugged. Leaning on generational characteristics predicted from their study of those 500 years, Strauss and Howe first named and described the social generations we know, including Millennials before most Millennials were even born.

Their work resonated immediately but isn’t a 10-minute read, so memes sprouted like weeds. The fact that generational memes are still flourishing more than three decades later says a lot about the foundational research; most contemporary memes aren’t relevant for more than a news cycle.

The theory behind the generations is far more sophisticated and clearly has staying power. We’ll attempt a short version with a few slides looking at the historical and social cycles—what Strauss and Howe called “turnings”—that are created by successive generations.

So—repeating cycles every 80 to 100 years of distinguishable ‘social moods.’ Young people coming of age at the time absorb and react to those moods, a new social generation is born, and turnings—identifiable eras—occur.5

Importantly, sociology, marketing, and leadership studies indicate these social generations may influence personality, values, attitudes and behaviors even more than families do. Peer environments during adolescence and early adulthood imprint deeply on individuals, forming a generational “personality” that influences attitudes toward authority, risk, community, and innovation. Generational cohorts often display synchronized shifts in political engagement, consumer behavior, and workplace expectations—again suggesting a shared lens that transcends family upbringing.

The “coming of age” part of this is critical. For most people, the coming-of-age years are about age 18 to mid-20s when the brain is undergoing a fundamental reorganization as it completes development and maturation.6 A critical interplay then of neurological, psychological, and social factors makes the brain particularly open to input from the environment. It’s a crucial stage of identity formation; experiences then have a powerful and lasting impact on adult behavior, personality, and mental health.7

It’s important to understand that while people born around the same time share common experiences, that doesn’t mean we all have the same reactions to those experiences. We’re all individuals, we experience events differently,8 and everyone changes over time. We’ll get more into the generations in Part 2, and Part 3 will be about how to deal with it all.

So, what Turning are we in now?

We’re solidly in the Fourth Turning, the crazy-making one.

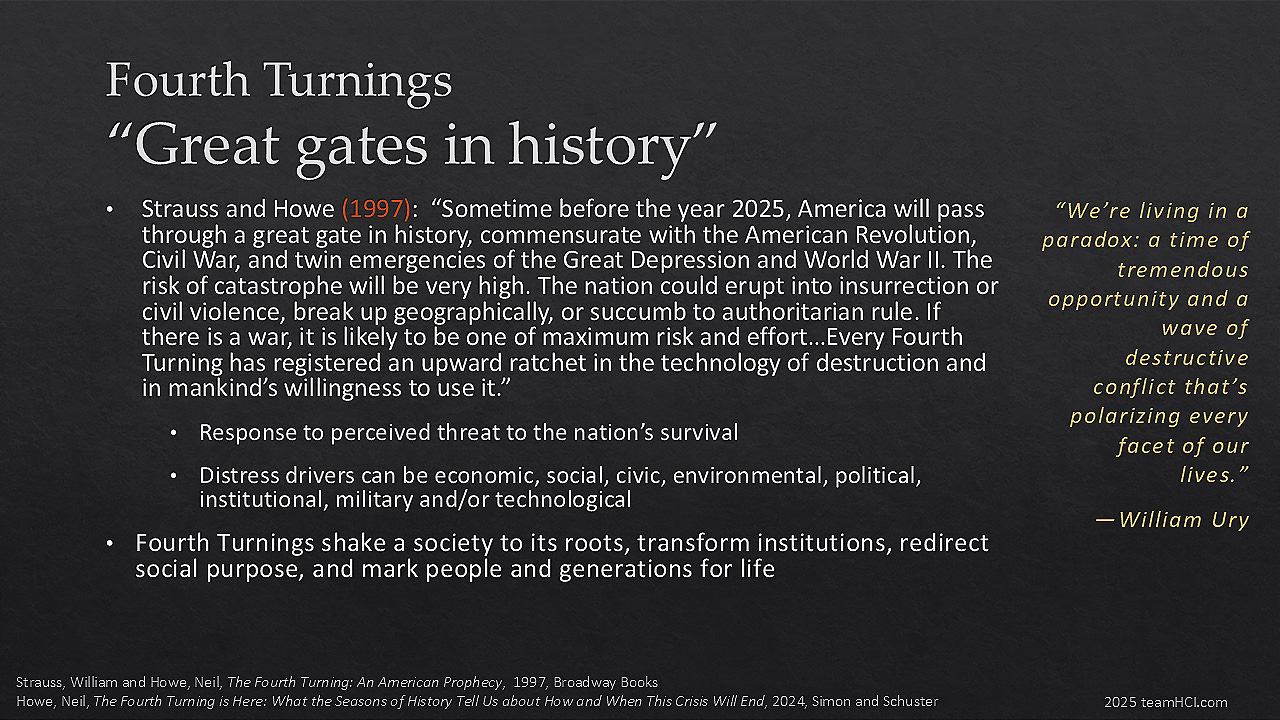

Way back in 1997, Strauss and Howe described what we’d be going through as a nation “sometime before the year 2025,” when they wrote The Fourth Turning: What the Cycles of History Tell Us About America’s Next Rendezvous with Destiny.

“Sometime before the year 2025” was a prediction in 1997 based entirely on what they’d found in the research about the prior five centuries. Pretty specific, no?

“Shakes a society to its roots.” And here we are.

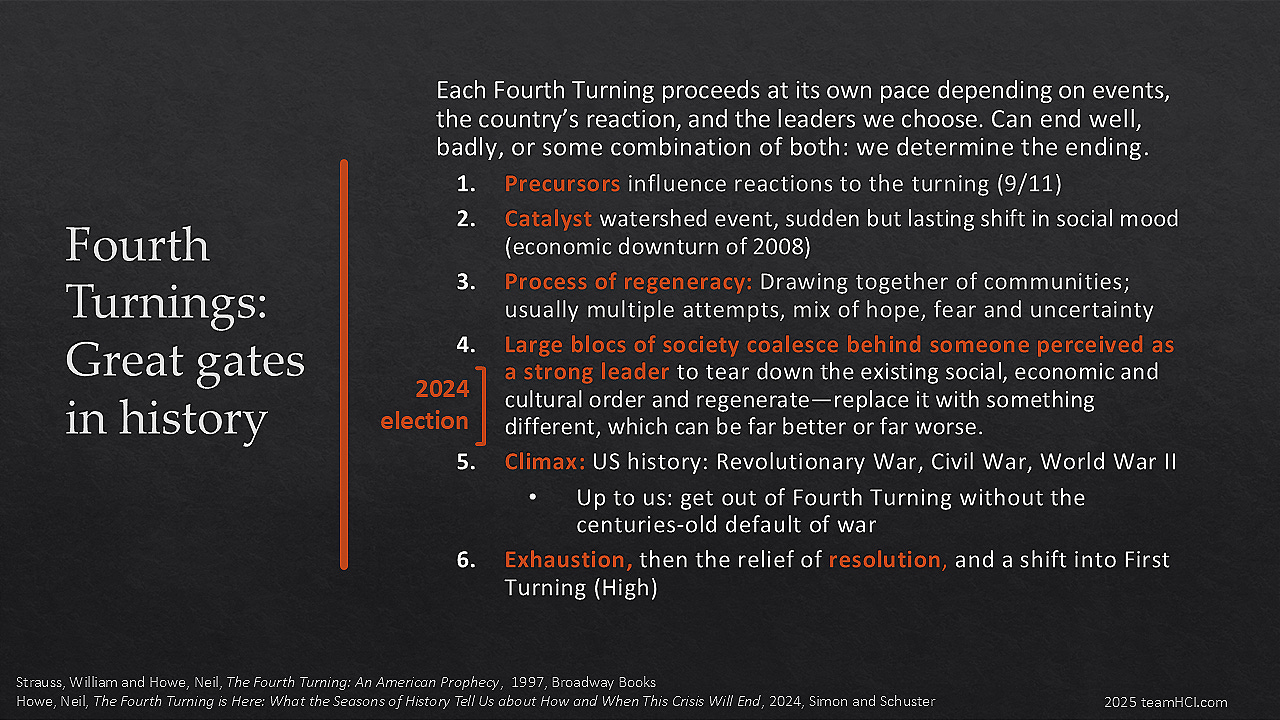

OK … but are we almost through?

Well, probably not. Here’s a summary of the phases of a Fourth Turning.

I know you’re exhausted already. So am I.

But it’s hard to see resolution anywhere in sight yet. No matter how much some try to act like the last election settled things once and for all, a polarized 50/50 electorate getting more so does not a resolution make. But we’ve absolutely been this divided before, and history says we will get there … one way or the other.

What that resolution looks like is up to us, with both a warning and immense possibilities. As William Ury says, “We’re living in a paradox: a time of tremendous opportunity and a wave of destructive conflict that’s polarizing every facet of our lives.” And sometimes the only way to define who you are is by figuring out who you are not—Churchill’s “everything else.”

For the record, Strauss and Howe’s research says turnings last, on average, about 20 to 25 years. Some longer, some shorter. You can do the math. And if you have the heart for much more on our current fourth turning, Howe has it in his most recent book, The Fourth Turning Is Here: What the Seasons of History Tell Us about How and When This Crisis Will End.

Two things that are reassuring when viewed through a generational lens:

We’re actually exactly where we’re supposed to be right now; centuries of similar cycles say we were going to lurch into some form of societal chaos right now; in fact, Strauss and Howe said it would occur before 2025—and that was back in 1997 when they said it.

The last time we massively reinvented our societal underpinnings was after the turn of the last century (the one starting with 19). All through the 1900s, we kept tweaking and tweaking what worked in the 20s through 60s—like someone returning over and over to the same restaurant where they once met the love of their life, hoping to meet another in the same place. In the meantime, those structures got worse and worse at handling changing needs and dramatically changing possibilities.

Now, after the industrial age, in a very different information age, those structures simply aren’t working for us any longer. We’re beyond tweaks. It doesn’t matter what societal structure you look at, from our post-WWII nuclear family structure9 to organized religion, legal or healthcare structures, college education and costs, political structures, or our economic structures or government. We have a mess that’s well beyond tweaking; it needed disruption and then reinvention.

We’ve certainly achieved disruption.

We absolutely have the right generations in place to deal with this—if we can look to a future more than a quarter’s earnings away and lift up younger generations to deal proactively with what we’ve created. That’s what Parts 2 and 3 are about.

What are your thoughts? What are you seeing? How do you keep it together right now?

Well, OK, except Boomers. We were convinced we’d never die—so, of course, why would we retire, right?

A Fever in the Heartland: The Ku Klux Klan’s Plot to Take Over America, and the Woman Who Stopped Them by Timothy Egan is an excellent, readable lens into that period in history.

No, not that ‘native’. Indigenous peoples who’d been in North America for 20,000 to 30,000 years weren’t viewed as ‘natives’ then, either; that’s not how colonization worked. The natives they meant were the WASPs who’d arrived a couple hundred years before from northwestern Europe, particularly England.

Prior US Fourth turnings: the American Revolution, the Civil War era, and the Great Depression and WWII.

A social generation is different from birth order or a specific number of years. Social generations are people who were born at about the same time in history, sharing significant historical, cultural and societal experiences. The shared experiences—even when experienced differently—are different than from other generations. Studying the events and social reactions of the time provides a framework for social analysis and historical interpretation. Unfortunately, it also provides a way to push the latest sneakers, and if you look up “generations” on the web, 99% of what you’ll see is there to sell something, not to help explain who we are and how we got to this point in civilization.

Maturation of the prefrontal lobe can be slower in individuals with behavioral issues, particularly those with problems linked to impulsivity, risk-taking and emotional regulation. For them, ‘coming of age’ can take much longer. I once heard a child psychiatrist say that for some people it can extend into their 40s—meaning they remain more susceptible much later in life to some of the cancers of social media.

Yes, it’s the same reason late adolescents/young adults are so easily attracted and influenced by both constructive and destructive social media. Or by enrolling in the armed services, or by any political or other outreach designed specifically to attract and mold malleable young minds. Here’s an overview of that.

For instance, the experience of White suburban adolescents and young adults during the 1960s was usually very different from the experience of Black urban kids then. But they both experienced the racial upheaval of the times—regardless of whether they participated in protests or watched them on TV from the ‘burbs—and they both formed values and opinions around it that are shared with others.

After WWII, the GI Bill made home ownership within reach of millions [of Whites] and led to rapid suburbanization. At the same time, cars and planes opened up travel like never before. Before that, American homes were multigenerational—not nuclear—with extended family in the same home or within a few blocks. Everyone kept an eye on the kids, a big reason kids were routinely ‘free range’ then. It does take a village to raise a family, and we never replaced that immediate family support. It’s a big piece of our record low birth rate—not the only cause, but a huge factor when you also consider our record low family and parenting support, the worst of 41 peer countries. Raising children is far easier as a team sport.

For more on why the GI Bill, ostensibly available to all GIs, was in reality denied to the vast majority of Black GIs, see impacts in housing and education.